Online Child Sextortion Is On The Rise, Law Enforcement Experts Warn

Since 2012, F.B.I. sextortion cases have increased almost 500 percent. Experts say children are at a heightened risk of becoming victims - and offenders' targets are getting even younger.

By: James Swift

UncommonJournalism@gmail.com

@UNJournalism

According to Michael Skapes, an intelligence analyst for the Federal Bureau of Investigation's Violent Crimes Against Children Unit, "stranger danger" has an entirely new definition these days.

"We always thought about the playground as the possible preying field for these offenders, but the reality of today is that the playground for these kids has changed," Skapes said during an Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention webinar on Nov. 9. "It's no longer in the physical form, but it's all online across all these websites and platforms."

He cited the case of Amanda Todd. An individual obtained a nude photograph of the 15-year-old Canadian and attempted to blackmail her into sending him more lewd images. When she refused, he made good on his threats and posted the photograph on the Internet.

Skapes said the image was sent to directly to some of Todd's closest friends and family members. Even after changing schools, Todd continued to receive threats from the anonymous stalker. The nonstop harassment resulted in the young girl committing suicide in 2012.

The case represents one of the more high-profile instances of online "sextortion" targeting minors - a crime F.B.I. officials say is increasing exponentially. Dr. Frank Kardasz, who serves as the Internet Crimes Against Children Task Force commander and a supervisory special agent for the State of Hawaii, said it consists of various elements of traditional extortion, harassment, cyberbullying and even hacking.

"It's a form of online sexual exploitation in which nonphysical forms of coercion are used, blackmail, in attempts to acquire sexual content - photos, videos," he said. "Sometimes to obtain money from the child or to engage in actual sex with the child victim."

The problem isn't exactly new. Legislators have zeroed in on the use of blackmail to sexually exploit children, Kardasz said, since 1986. However, the ubiquitous nature of the Internet - and especially the rise of social media - has not only made it easier for sextortionists to prey upon children, it has allowed them to target even greater numbers of victims.

And as demonstrated by the case of Lucas Chansler, they sometimes ensnare hundreds of children.

"He had 240 victims in 26 U.S. states, three Canadian provinces and the U.K.," Kardasz said. "He was a 31-year-old guy, he lived with his parents, he posed as a 15-year-old boy when he went on the Internet. He said he targeted 13-to-18-year-olds because older women were too smart for his scam."

In 2014, Chansler was sentenced to 105 years in prison for producing child pornography. Investigators, Kardasz said, recovered more than 80,000 images from his possession.

And there are far more child sextortionists out there.

"In the last four years," Skapes said, "the F.B.I. sextortion caseload has increased 472 percent."

The scope of the problem

Kardasz highlighted some recent literature on child sextortion findings.

A Crimes Against Children Research Center survey of about 1,600 victims found that 82 percent of those victimized online were female. Some respondents likened their experiences to being in a controlling, emotionally abusive relationship. "The suspects keep these pictures and use them to continue to abuse their victim," Kardasz noted.

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children examined data from more than 800 cyber-tip line submissions from 2013 to 2015. The average age of victims was 15, with some reported as young as just 8-years-old.

A Brookings Institution review of 78 sextortion cases across the globe found that 91 percent of incidents involved some form of social media manipulation - specifically, "catfishing" - while 43 percent involved hardware being hacked. Most sextortionists, the research found, were prolific and repeat offenders. Four of the individuals examined had more than 100 victims.

A National Academy of Sciences report took a look at the impact of online harassment on young victims. Anxiety, sleeping disorders, prolonged cyberbullying and suicide ideation were frequent consequences.

"These victims fear law enforcement because some of the suspects are telling them, 'hey, you've created child pornography so now you are a suspect,'" Kardasz said. "The victims are too young to understand that we in law enforcement are not going to come after these kids. We want the suspect."

While Kardasz said he isn't aware of many "sextortion" laws on state books, those who commit the offense are almost always prosecuted on formal extortion charges. And since many child sextortion cases involve "an interstate nexus," Kardasz said many offenders are prosecuted on the federal level. "Your emails, your social networking messages, they don't just travel within your state," he said. "Those messages are bouncing off of servers in lots of different states across the U.S."

There are some barriers to prosecuting sextortion offenses against children. Sometimes, Kardasz said victims themselves don't want to take their cases to court - having to speak at trial is too humiliating or painful. Additionally, some Internet Service Providers aren't willing to comply with "preservation letters" or hand over suspect data. Encryption sometimes makes it difficult to track down suspected offenders - especially those who conduct business on the so-called "Dark Web," where users Internet Protocol addresses are "hidden" via anonymity software like Tor. And there is little U.S. law enforcement can do when suspects are overseas. [See section "Operation: Strikeback" for more information on how U.S. law enforcement deals with international cases.]

While those convicted under federal child pornography offenses are guaranteed at least 15 years behind bars, the severity of penalties for state crimes fluctuates wildly - even when enhanced sentencing for crimes against children are in play.

"When I worked in Arizona, there was a mandatory minimum of 10 years in prison for one image," Kardasz said. "In Hawaii, we're seeing offenders on child pornography cases get a day in prison."

The predatory process

A 2015 article in Glamour profiled Ashley Reynolds, one of Chansler's many sextortion victims. Thirty readers came forward claiming they may have been one of his victims as well.

"They were victims of sextortion, however they were not Chansler's victims," Skapes said. "It speaks to that growing threat, the growing number of subjects who are doing this to target children."

Whereas the average child pornography offender is 38, Skapes said those who commit child sextortion tend to skew younger, with the average subject just 24 years-old.

While some sextortionists get their images and videos via hacking, the bulk of offenders obtain them via "social engineering." They begin by stealing an image of a young person and posting it as their social media avatars - interestingly, Skapes said F.B.I. data indicates about half of child sextortionists pose as underage females. From there, they go on mass "friending" sprees to accumulate as wide a pool of potential victims as possible. Then the grooming begins. They start chatting with soon-to-be victims and convince them to send them images. And when they have one sexually explicit photo, that's usually all they need to start sextorting.

Most sextortionists who target children aren't in it for money. Instead, they want victims to feed them a steady stream of sexual content, including long-form videos on platforms like Skype.

"Kik is a great app for these subjects to use because it's semi-anonymous, it's a great meeting place for subjects for children," Skapes said. And with children virtually tethered to the Web through mobile technology, sextortionists practically have 24/7 access to their victims.

"We're not talking about two or three photographs a day, these subjects demand 50, 60, 100 different photographs a day - very explicit, very focused requests on what they want these children to do," Skapes said. "Numerous times these children have said they were made to go into the bathroom at school and produce images."

Even more disturbing, Skapes said primary child victims are frequently cajoled into abusing younger siblings and obtaining photos and videos of other young acquaintances for the sextortionist's "amusement."

He brought up the case of Joshua James Geer, a Cartersville, Ga. resident who was sentenced to 30 years in prison in 2014. Not only did he sextort minors, an F.B.I. investigation revealed his plans to abduct and sexually torture young victims.

So heinous his crimes, United States Attorney Sally Yates remarked "he is the type of predatory monster parents fear when their children are on the Internet. He deserves every day of the sentence the court imposed."

Close to 20 percent of online child sextortionists, Skapes said, are either actively abusing children in "real life" or attempting to physically get their hands on underage victims.

Skapes said F.B.I. data indicates that 78 percent of sextortion victims are between the ages of 14 and 17. Nearly a quarter are under the age of 13.

"Children are becoming more adept at using technology at a younger age," he said, "and I really believe that piece of the pie - the 22 percent that's 13 or younger - is going to increase and grow over time."

Operation: Strikeback

Sextortion isn't just a devious method for child predators to take advantage of young victims, however. Homeland Security Investigations Criminal Investigator Bruce Law recounted how, in the Philippines, it's a remarkably lucrative criminal operation.

In 2013, Scottish teen Daniel Perry began corresponding with an online "friend" he thought to be a teenager from Illinois. After recording some risque webcam content, he received threats from individuals demanding they send him money, or else the video would be released to his family and friends.

"The 17-year-old male victim was told he might as well commit suicide if he didn't pay," Law said. "Which, shortly thereafter, he jumped off a bridge to his death."

The INTERPOL Digital Crime Centre - working in close cooperation with the Philippines National Police and several other law enforcement agencies - traced Perry's sextortionists back to Luzon. There, investigators found an enormous blackmail racket, operating on what Law described as a commercial scale.

"There are at least 100 victims from different countries," he said. "That included victims from the U.S.A., Hong Kong, Singapore, England, Australia and also, other parts of the European Union."

A massive INTERPOL sting, code-named "Operation Strikeback," identified nearly 200 people working for three organized crime syndicates in the Philippines in stings conducted in early 2014.

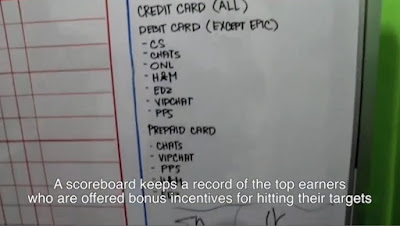

"Employees" were being trained on how to catfish people on Facebook. They received bonuses for hitting sextortion quotas; according to INTERPOL, spreadsheets and whiteboard etchings revealed blackmailers were demanding victims transfer as much as $3,000 to avoid having photos and videos leaked. Further investigation revealed similar wide-scale "sextortion" operations in Africa, almost exclusively targeting victims in Europe.

"These perpetrators were operating on an almost industrial scale, in call-center style offices," Law said. "A big commercial type office, filled with cell phones and computer screens."

'It lasts there forever'

The consequences of sextortion are devastating, Skapes said.

"We often see depression, substance abuse, performing poorly in school," he said. "We even had one young girl who starved herself because she thought by starving herself, she would be admitted to the hospital and she'd finally be out of the grasp of her subject."

He said about half of sextortionists follow up on their threats to release damaging images or videos. Some are so adept with technology they create virtual masks to facilitate live video chats with unassuming prey.

The F.B.I. research, he said, paints no specific victim profile - seemingly, child sextortionists simply go after whoever makes themselves available.

Law said teens, tweens and even elementary schoolers are posting far too much personal information on social media platforms. Potential sextortionists have at their disposal a gold mine of information - a child's likes, dislikes, even what schools they attend.

"Once they befriend them, then they have their hooks in," he said. "A lot of times they think it will stop if they don't do anything. But it never does stop."

Offenders capitalize on the naivety and vulnerability of young victims, Kardasz said. Often, all it takes are a few compliments and a little feigned interest in children's interests and teens and adolescents will let down their defenses.

Although there are technical procedures that can be taken to deter child sextortion - i.e., turning off devices when not in use, covering up webcams, making sure operating systems are up to date - Kardasz said the best safeguard remains observant parents.

"We can continue to tell them the thing we've always been telling them - it's the tired old song of 'watch your kids around computer,'" he said. "In the case of sextortion, we want them to be empathetic. We want them to not be punitive because we really want to save kids' lives and we know just adding to the depression and the humiliation these kids feel is not going to help them."

Even after an offender has been arrested, he said photographs of victims on the Internet are likely to continue being circulated. "Every moment they are up there, some other person can be - and is - copying those and posting them somewhere else," he said.

Steffie Rapp, an OJJDP juvenile justice specialist, said that while it's developmentally appropriate for preteens and teens to explore their sexuality, they should not be doing so via the Internet.

"Nowadays, because technology is so embedded in youths' lives, that for a child, we have to make sure that we know that they are developmentally in a place where they want to start exploring their sexuality, but they absolutely can't do it online," she said. "Because it doesn't become just a moment in time that then becomes a memory, if they do something online, it lasts there forever."

|

| Uncommon Journalism, 2016. |

Comments

Post a Comment